The most important factor in the mental health of adolescent children is the quality of the relationship with their caregivers. This, in turn, is strongly related to parenting practices—with the best results coming from warm, responsive, and rule-bound, disciplined parenting.

Originally published by the Institute for Family Studies

After a decade of surging adolescent mental health problems and suicide, the nation’s leading public health authorities have declared an emergency. Unfortunately, the solutions proposed by organizations like the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics—such as increased funding for diagnostic and psychiatric services—do not meet the challenge and ignore what are likely to be the most important causes. Adolescent biology hasn’t changed.

My colleagues and I at Gallup launched a study this summer to understand the causes. We surveyed 6,643 parents, including 2,956 who live with an adolescent, and we surveyed an additional 1,580 of those adolescents. We asked about mental health, visits to doctors, parenting practices, family relationships, activities, personality traits, attitudes toward marriage, and other topics, including excessive social media use, as discussed in prior work. I present the results in a new Institute for Family Studies and Gallup research brief.

The findings are clear. The most important factor in the mental health of adolescent children is the quality of the relationship with their caregivers. This, in turn, is strongly related to parenting practices—with the best results coming from warm, responsive, and rule-bound, disciplined parenting. The data also reveal the characteristics of parents who engage in best-practices and enjoy the highest quality relationships.

When it comes to the quality of parenting practices and the quality of child-parent relationships, there is no variation by socioeconomic status. The results may be shocking to many highly educated Americans who were taught to believe that socioeconomic status dictates everything good in life. Income doesn’t buy better parenting, and more highly educated parents do not score better, either. Parenting style and relationship quality also do not meaningfully vary by race and ethnicity within our U.S. sample.

These results are not unique to the Gallup sample. In 1997 and 1998, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics collected summary data on adolescent parent-child relationships. My analysis of these data shows that parental income, wealth, and race/ethnicity don’t bear any relationship with the parenting measures predictive of the long-term well-being of children. Education explained less than 1% of the variation.

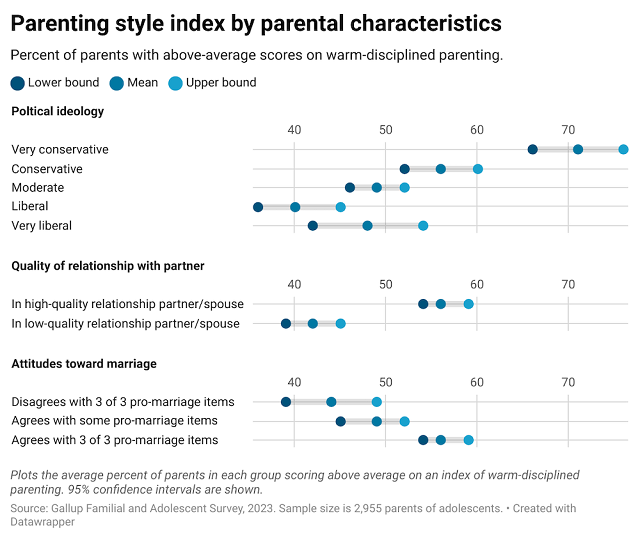

Note: View the figure here.

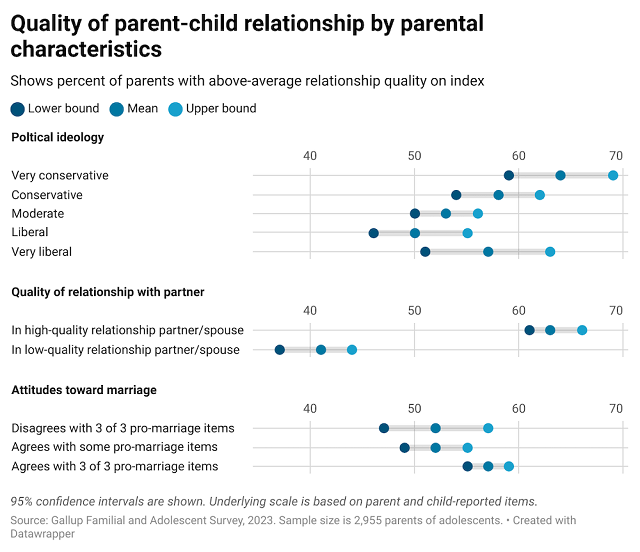

Yet, some parental characteristics do matter. Political ideology is one of the strongest predictors. Conservative and very conservative parents are the most likely to adopt the parenting practices associated with adolescent mental health. They are the most likely to effectively discipline their children, while also displaying affection and responding to their needs. Liberal parents score the lowest, even worse than very liberal parents, largely because they are the least likely to successfully discipline their children. By contrast, conservative parents enjoy higher quality relationships with their children, characterized by fewer arguments, more warmth, and a stronger bond, according to both parent and child reporting.

Aside from political ideology, parents who think highly of marriage—by disagreeing that it is an outdated institution and agreeing that it improves the quality of relationships by strengthening commitment—exhibit better parenting practices and have a higher quality relationship with their teens. Parents who wish for their own children to get married someday also tend to be more effective parents. Those who embrace a pro-marriage view on all three have the best outcomes.

Other relationships seem to affect the current child-parent relationship. Parents who give high ratings to their relationship with their spouse or romantic partner are also more likely to adopt best practice parenting strategies and enjoy higher quality relationships with their teens.

Note: View the figure here.

While nationally representative summary data on parenting is rare, the foundation of this report rests on decades of research. Even though there are biological and genetic risk-factors for every disease, even mental health conditions, years of research have established that parenting—and the parent-child relationship—is of paramount importance to the well-being and psychological functioning of adolescents.

In particular, the late Stanford University psychologist, Eleanor Maccoby, her colleagues, and students found that children raised by responsive, but limit-setting parents have the best outcomes. They described this style of parenting as “authoritative”—and distinguished it from permissive and authoritarian forms of parenting, which were not as successful. Children raised in authoritative homes are more likely to exhibit self-control, social competence, success in school, compliance with rules and reasonable social norms, and even exhibit more confidence and creativity. Hundreds of subsequent empirical studies show that depression, anxiety, and behavioral problems are significantly lower when children experience this form of authoritative parenting.

Returning to the present crisis, it would appear as if this scholarship has been forgotten. No effort is being made by leading public health organizations to inform parents about what works to prevent depression, anxiety, or behavioral problems in teens. Federally-funded evidence-based dietary guidelines offer clear suggestions about the composition of a healthy, balanced diet, or the right amount and type of exercise to achieve optimal health. Many of these recommendations could be characterized as common sense, often passed down over generations, with modest refinements, as new and better research becomes available. Yet, when it comes to teen mental health, the implication is that medical experts are the only people who can prevent illness or help if it arises—often with prescription drugs. Expert-led services that could heal relationships—through family or individual therapy, for example—are often not even covered by health insurance, in part because reimbursement rates are too low. Parents are disempowered and sidelined, and yet social science continues to show that their actions, judgments, and relationships are the key to their teen’s mental health.

Download the full IFS/Gallup research brief here.

Jonathan Rothwell is the principal economist at Gallup and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.